DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

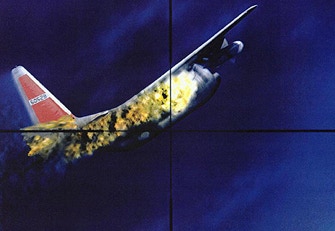

Airborne Peripheral Reconnaissance, Cold War Losses

“Silent Sacrifices”

USAF RB-47H , Barents Sea, July 1, 1960

On July 1, 1960, a Soviet MiG-19 flown by Vasili Poliakov shot down an RB-47H (53-4281) electronic reconnaissance mission over the Barents Sea between the Kola Peninsula and the Soviet island of Novaya Zemlya. The aircraft and crew were from the 343rd SRS, 55th Reconnaissance Wing, home-based at Forbes AFB, Kansas. They flew this mission out of RAF Brize Norton, United Kingdom. Six souls were aboard.

Maj Willard Palm, aircraft commander; Capt. Freeman Bruce Olmstead, pilot; Capt. John McKone, navigator; and three reconnaissance officers (Raven-ELINT operators): Maj. Eugene Posa, Capt. Dean Phillips and Capt. Oscar Goforth.

The website This Day In Aviation said Olmstead and McKone were rescued by a Soviet trawler, jailed, interrogated, and later released. Posa’s and Palm’s bodies were recovered. Posa’s body was sent to Severomorsk and then on to Moscow. He was buried in an “unknown cemetery.” Palm’s body was returned to the US. Goworth and Phillips were never found and presumed KIA.

Olmstead and McKone were imprisoned at Moscow’s Lubyanka prison in separate cells, accused of espionage for violating the Soviet frontier. They said they were interrogated daily, but managed to resist answering the revealing questions about their work. The Soviets released them seven months later.

McKone suffered severe back injuries and spent 97 weeks in traction.

The Aviation Geek Club reported,

“The RB-47H carried three Special Operators in a pressurized bomb-bay capsule. The aircraft’s primary Elint system was the APD-4 automatic receiver/analyser, supplemented by manually-operated APR-17 receivers, an ALA-6 direction finding (D/F) system and ALA-74 pulse analysers.”

The three reconnaissance officers (Special operators) were unable to eject.

FAS Intelligence Resource Program reported,

“(RB-47s) were used to constantly check weather along projected bombing routes, photograph enemy installations and monitor defensive radar systems.”

The RB-47 launched from RAF Brize Norton five hours before it was attacked. It flew north along the coast of Norway and entered the Barents Sea, turning southeast to follow a preplanned flightier route parallel to the Kola Peninsula, Kolguyev Island, and Novaya Zemlya. The RB-47 passed Murmansk about 15 minutes before the attack.

The website This Day In Aviation said,

“The RB-47’s navigator, Captain McKone, recalled that he had just taken a radar fix of their position when the MiG-19 attacked. 53-4281 was flying at 28,000 feet ( meters) at 425 knots, 50 miles north of Cape Holy Nose, the northern end of the Kola Peninsula. Their course was 120° (southeast). McKone had given Captain Palm two minor course corrections, both to the left, away from Soviet air space. The American reconnaissance was definitely in international air space. (The Soviet Union claimed a 12 nautical mile territorial limit.)

“The RB-47H was being tracked by NATO ground based radar (probably from Norway). The chart shown is an ‘accurate radar plot of the RB-47’s ground track obtained from a ground-based radar tracking facility.’”

Oleg Penkovskiy, a senior Soviet military intelligence officer who spied for British and American intelligence in the early 1960s, said this:

“The US aircraft RB-47 shot down on Khrushchev’s order was not flying over Soviet territory; it was flying over neutral waters…When the true facts were reported to Khrushchev, he said: ‘Well done boys, keep them from even flying close.’ “

Vasili Poliakov, the MiG-19 pilot who shot down the RB-47, was from the 206th Air Division at Murmansk. He was sitting strip alert when scrambled. He flew at a distance parallel to the RB-47, then turned toward her on an intercept course, but about three miles behind her.

Capt. McKone, the pilot, was about to turn to the northeast when the MiG returned and approached the RB-47 in close formation, at about 40 ft. off the right wing of the RB-47. He rocked his wings to tell the RB-47 crew to land, which the American crews were told not to do. The RB-47 gave no response, so the ground controller gave the command to destroy the aircraft. The RB-47 was at 30,000 ft. and 425 knots and turned to his left.

The MiG-19 turned right toward the shoreline, then turned back toward the RB-47 and opened fire. He hit the left wing, two of his three starboard engines, and fuselage on his first pass. Both engines were lost. That sent the RB-47 into a tailspin. The two pilots, Palm and Olmstead, were able to stabilize the aircraft, and Olmstead opened fire with his tail guns, but he was no match for the MiG-19.

The MiG-19 made a second firing pass to finish her off. The RB-47 pilots again tried to stabilize the aircraft but failed, and the skipper ordered a bailout. It is thought the three reconnaissance officers were trapped in a converted bomb bay with their equipment and were unable to bail out.

There were considerable communications intelligence COMINT intercepts of the event. The Norwegians provided voice intercepts. An advisory warning under the new program was issued but if it reached the crew at all, it would have been too late.

Francis Gary Powers and his U-2 aircraft were shot down by Soviet surface-to-air missiles (SAM) on May 1, 1960. This RB-47 shootdown occurred just two months later. The Prop Wash Gang has highlighted President Eisenhower’s reactions to this new shootdown. He learned of the shootdown from Newport News tickers on July 11, eleven days after the event. He was irritated, and questioned the validity of what the military would tell him.

Eisenhower spoke by telephone with Secretary of State Christian Herter on July 12. A memorandum of the conversation said this about Ike’s reaction,

“The President said they say we never got out of international waters and never went over Soviet territory and how can you say that if you don't know where the plane was (the aircraft was on radio-silence). The President said it seemed to him their (Air Force and CIA) argument is silly. He went so far as to suggest Britain take up such flights in the future.

On the heels of the U-2 shootdown, US reconnaissance flights targeted against the USSR came under greater scrutiny by the Governments of Britain and Norway. The Aviation Geek Club reported,

“It emerged that the UK was not given the route of US Elint sorties in advance, but were normally given the Navigator’s log and intelligence results from each flight some time afterwards. As such the Air Ministry was only aware in general terms of the likely aircraft track of any sortie. The Air Ministry were later passed the flight plan for the Jul. 1 RB-47H sortie, along with ground intercepts of Soviet air defence activity, including tracking data. From this it appeared that the plan had been to keep 60nm (111km) from the Soviet coast, although intercept evidence suggested the RB-47H had actually closed to 28nm (52km) before resuming its planned track, then standing off some 66nm (122km). Tracking data was inconsistent, but appeared to show the aircraft may have closed the coast again before being shot down.”

Time Magazine reported,

“With Khrushchev away touring Austria, First Deputy Premier Anastas Mikoyan and his lieutenants in the Kremlin dithered for ten days over what to do about the downed RB-47. For reasons best known to themselves, they said nothing. In fact, they sent a cruiser out to play a grisly farce of helping the U.S. and Norwegian air forces look for the survivors.

“Then Khrushchev returned and fired off an abrupt note informing the U.S. that a Soviet fighter plane had shot down the RB-47 near the Kola Peninsula.”

The Soviets handed a note to Britain’s ambassador in Moscow on July 11, 1960. It protested the use of British bases for these flights. There was considerable debate in the House of Lords,

“The Moscow announcement came as a genuine surprise to British and United States authorities. The act was described in Defence Ministry circles as appalling'. Nothing was known of the whereabouts of the aircraft, and the 10-day search was a genuine one. The Ministry spokesman reiterated that the flight was a perfectly legal one for scientific purposes, and the route was known to the Ministry. It is in fact virtually impossible for any clandestine mission to be made by a foreign aircraft from a British base, since the flight plan must be made known and all necessary steps taken to ensure the aircraft's security.”

Questions were raised about Britain’s “working arrangements” with the US; “there has existed for some time a working arrangement by which American aircraft can use our bases with or without our having knowledge of these flights?” Concerns were expressed that Britain might be seen as a “party to this business.”

The Prop Wash Gang commented,

“The United States and Norway also reviewed U.S. reconnaissance flights touching Norwegian territory. A memorandum of conversation between Secretary Herter and Norwegian Foreign Minister Halvard Lange on October 10 indicated that the United States agreed to give Norway advance notice of U.S. peripheral reconnaissance flights through military-to-military channels.”

Henry Cabot Lodge, the US ambassador to the UN, saw the COMINT intercepts of Soviet tracking of the RB-47. That tracking showed the aircraft “still in the air twenty minutes (after the attack), over the high seas, 200 miles from the point alleged by the Soviet Union and flying in a northeasterly direction.”

__________

Click to zoom graphic-photo

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- USN PB4Y2, Baltic Sea, April 8, 1950

- USN P2V Neptune, Sea of Japan, November 6, 1951

- USAF RB-29, June 13, Sea of Japan, June 13, 1952

- USAF RB-29, Sea of Japan, October 7, 1952

- USAF RB-50, Sea of Japan, July 29, 1953

- USN P2V, Sea of Japan, September 4, 1954

- USAF RB-29A , Sea of Japan, November 7, 1954

- USAF RB-47 , off-shore Kamchatka Peninsula, April 18, 1955

- USAF RB-50G , Sea of Japan, September 10, 1956

- USAF C-130A , Soviet Armenia, September 2, 1958

- USAF RB-47H , Barents Sea, July 1, 1960

- USAF RB-66C , East Germany, March 10, 1964