DUTY, HONOR, COURAGE, RESILIANCE

Talking Proud: Service & Sacrifice

Airborne Peripheral Reconnaissance, Cold War Losses

“Silent Sacrifices”

USAF RB-66C , East Germany, March 10, 1964

Three, possibly four, Soviet fighters based at Wittstock and Zerbst, East Germany, attacked and shot down a USAF RB-66C serial nr. 54-0451 near Gardelegen, East Germany, on March 10, 1964. The RB-66B violated East German airspace. It had three crew, all bailed out, were captured, and repatriated days later.

The RB-66B from the 19th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron (TRS) launched from Toul-Rosieres Air Base, France. The crew included Capt. David Holland, pilot; Capt Melvin Kessler, navigator instructor; and 1st Lt Harold Welch, listed as a navigator and electronics officer, but probably a photo camera operator.

The RB-66B was configured as a photoreconnaissance aircraft. The film camera equipment was mounted in the belly. The RB-66B carried flash bombs in its bomb bay for night photography missions. Depending on the mission, it could carry various cameras, such as high and low.

The website spyflight.co.uk reported that the RB-66B was “on a routine navigational training sortie.” It continued,

“The aircraft was flown by an experienced pilot named Capt. David I Holland, and acting as his navigator was Capt. Melvin J Kessler, one of the senior navigators of the wing carrying out a combat qualification check on the third member of the crew, Lt Harold W Welch. The plan was to fly a high-low-high mission to conduct a low-level photo run on several bridges and rivers in northwest Germany, near the town of Osnabruck.

“At approximately 100-150 miles from Toul, as the VOR/DME navigation aid on the RB-66B became ineffective, the aircraft slowly climbed to 33,000ft, and the autopilot was engaged. At this stage of the sortie, they were flying over an undercast and were relying on Lt. Welsh to determine the aircraft's position by interpreting the returns he could see on the aircraft radar; however, in such a heavily populated area, this was a very difficult task. Capt. Kessler was cross referring the estimated radar position by using the latitude and longitude positions displayed on the aircraft’s Doppler navigation system. In reality, rather than flying over the north German plain in West German airspace, the aircraft was flying into the central air corridor heading towards Berlin, entering East German airspace.”

The Aviation Geek Club reported,

“Two Wittstock-based…Mig-19s were on Combat Air Patrol in their Northern sector when the RB-66’s intrusion was detected. Two more MiG-19s were launched by the Zerbst-based Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) flight and intercepted the RB-66 before the Witstock aircraft did. As the US aircraft turned westwards, Kapitan FM Zinoviev was told to engage it and brought it down with a salvo of four S-5 unguided rockets followed by canon fire.”

The Aviation Geek Club has posted Zinoviev's recollections. He said he took off on afterburners, which was unusual and had not retracted his gear when he was told, “Steer course 330, the target is hostile; arm your weapons.” He said he “fired his 23-mm canon in a rear-quarter attack from below as the target passed ahead of me. I finally ceased fire about ten kilometers from the border. The enemy aircraft exploded, and in the haze of the setting sun, three red-and-white parachutes blossomed.”

A USAF fact-finding board reported that “a gross navigation error result from the N1 compass system led the crew to believe they were on a correct magnetic course when they were not … (There was also a) lack of complete crew coordination and failure to cross-check the plane’s position by other navigational means available.”

US controllers in West Germany followed the RB-66 closely and tried to warn the crew to return but received no acknowledgment.

Major Verne Gardina, a highly respected RB-66 navigator, investigated the incident. The website spyflight.co.uk reported that he determined the following:

“The cause of the navigation error was eventually narrowed down to the RB-66's compass system. Maj Verne Gardina had experienced a similar error before, but luckily it happened over the USA and not East Germany. He proved that if the RB-66 delta-wound N-1 Compass system mounted in the left wingtip malfunctioned, once the auto-pilot was engaged, the aircraft would drift further and further to the right - exactly what had happened to Capt. Holland's aircraft. Maj Verne Gardina's detailed investigation into this incident proved that the aircraft equipment, rather than the crew, was at fault, and Capt. Holland and his crew were cleared of all responsibility for the loss of the RB-66B. Capt. Holland returned to flying duties and in the Vietnam War is credited with 146 missions in the EW version of the RB-66, the EB-66.”

The RB-66 was shot down near Gardelegen, East Germany, close to the Letzlinger Heide training area, one of the largest military training areas in East Germany. The Soviets conducted a significant exercise there when the RB-66 flew its mission. As a result, some believe the RB-66 was collecting intelligence on this exercise. Perhaps coincidentally, the Soviets were also preparing to conduct a series of simulated nuclear strikes on the area of Stendal, East Germany. The RB-66, with a tactical photoreconnaissance capability, was flying directly toward Stendal, making a descending pass.

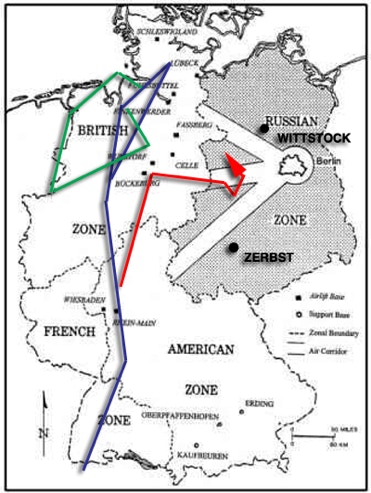

The blue track on this map shows the planned course for the high-level track and the green for the low-level track. The red track depicts Soviet tracking of the actual flight route into East German airspace. You will recall the fighters launched from Wittstock to the north and Zerbst to the south.

The Soviets tracked the RB-66, and about 14 minutes before being shot down, it made a sharp right turn off its northern flight route and proceeded east, straight into East German airspace. The RB-66 turned to the southeast, departed the Berlin corridor, and turned sharp to the north. The Soviets attacked when the RB-66 was somewhere between 21,000 and 14,000 ft.

Once the Soviets saw the RB-66 approaching the East German border, the Northern Fighter Corps (NFC), which already had one MiG-19 from Wittstock on a defensive patrol, scrambled another. Both headed toward the RB-66. The Southern Fighter Corps (SDFC) also scrambled two MiG-19s out of Zerbst about two minutes before the RB-66 entered East German airspace.

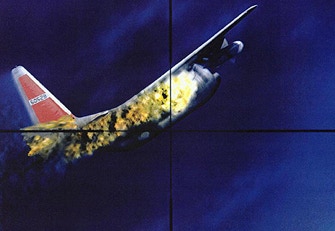

The Soviet pilots reported seeing the target. One said he was flying with the RB-66 and would start his attack run. He reported overtaking the RB-66 and had readied two cannons. He then reported the “intruder” turning to the left, said it was a swept-wing jet, told the ground controller to move another MiG-19 away from him so he did not shoot him, and then said he fired and hit the target. One of the pilots, perhaps that one, said he would attack again and reported the aircraft as a B-66. They said it was burning, going down, banking somewhat to the right, going then into a left turn with its bank getting steeper. The pilots reported seeing chutes open, first two, then three, and then reported the aircraft crashing and exploding on the ground.

The French SIGINT site at Berlin-Tegel “recorded the RB-66 flying towards the Inner German Border (IGB) and then being downed by the MiGs.” The French account “suggests that the RB-66 was operating near the entrance to the Central Corridor, where they believed it was attempting to identify a new Soviet radar.”

The signals intelligence (SIGINT) community gained much knowledge from this attack. The National Security Agency’s (NSA) report, “Maybe you had to be there,” said,

“Fourteen minutes before being shot down, the RB-66 made a sharp right turn off its northern flight route and proceeded due east, entering East German airspace on a track placing it equidistant from the northern and southern borders six minutes later. The reconnaissance plane then took a southeasterly heading, departed the corridor, and quickly cut back sharply to a due north heading while beginning a descent from about 33,000 feet. Before changing to a northwesterly heading at about the same time it was attacked, the RB-66 was in descent between 21,000 and 14,000 feet.”

The Army Security Agency (ASA) and USAF Security Service (USAFSS) had multiple ground stations near the East German border or West Berlin. They all picked up a good deal of Soviet-East German VHF air-ground voice, UHF multichannel clear voice, conventional tracking, tracking employing a special data system known as SWAMP, ELINT from one of the fighter’s airborne intercept radars, known as Scan Odd, in the firing mode, and Berlin Corridor controller communications trying to alert the RB-66 to an impending attack.

NSA continued,

“As the RB-66 approached the East German border, the Northern Fighter Corps (NFC)…had one Wittstock-based MiG-19 fighter already airborne in a defensive patrol and immediately launched a second. Both were vectored toward the intruder. The Southern Fighter Corps (SFC)…scrambled two Zerbst-based MiG-19s about two minutes before the RB-66 entered East Germany. The NFC MiG-19, on a defensive patrol, was the first to spot the RB-66 just as it crossed the border.

“Both pairs of fighters intercepted the RB-66, and at least three interceptors made firing passes, occasionally getting in each other’s way…Their respective GCI (ground-controlled intercept) controllers were aware of the other pair’s activities and locations and attempted to coordinate their attacks.”

The US Military Liaison Mission (USMLM) in Berlin was put on alert at 1700 hours on March 10, 1964, and by 1745 hours, had learned that an aircraft, probably the RB-66, had crashed. The crew had probably parachuted, landing in East Germany. The USMLM organized three search teams and notified the Soviet External Relations Branch (SERB) that the teams had been dispatched to search for survivors.

The Soviets, on March 11, claimed no knowledge of the aircraft or its crew. However, local East Germans said two from the crew parachuted safely, and the third was taken to the Gardelegen hospital.

The USMLM arranged, with difficulty, to meet with the Chief SERB late in the evening of March 11 to deliver a note from General Paul Freeman, USA, commanding general of US Army Europe, to General Ivan Yakobovsky, commander of the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany.

The search teams returned to Berlin on March 12 after surveilling the area between Gardelegen and Potsdam. The USMLM asked for permission to visit the Gardelegen hospital. The Soviets stone-walled all USMLM requests until March 16. On March 16, the Soviets informed the USMLM that a USAF military officer suffering from bruises and a broken leg was receiving aid at a hospital in Magdeburg. The Soviets advised that an American medical officer would be permitted to visit this officer. As mentioned earlier, the US hospital commander in Wiesbaden visited Lt. Welch on March 16.

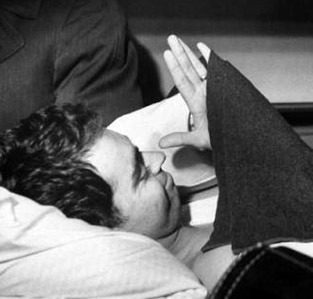

The Soviets allowed medical visits on March 17 and 19. On March 21, the USAF medical officer accepted custody of the patient, transported him to the Helmstedt Checkpoint, and then off to Wiesbaden by USAF aircraft. This photo shows Lt. Welch being transferred to the hospital from a USAF evacuation aircraft. His broken right arm is not in this photo.

The status of the other two crew members remained unclear. East German newspapers had reported that they would be tried for espionage. On March 17, the Chief SERB notified the USMLM that they would return the two crew members to US custody on March 27. The USMLM accepted custody of the two crew members and transported them to West Germany. The photo shows Capts. Holland (left) and Kessler (right) after their release.

The US was not able to recover any of the RB-66 wreckage.

__________

Click to zoom graphic-photo

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- USN PB4Y2, Baltic Sea, April 8, 1950

- USN P2V Neptune, Sea of Japan, November 6, 1951

- USAF RB-29, June 13, Sea of Japan, June 13, 1952

- USAF RB-29, Sea of Japan, October 7, 1952

- USAF RB-50, Sea of Japan, July 29, 1953

- USN P2V, Sea of Japan, September 4, 1954

- USAF RB-29A , Sea of Japan, November 7, 1954

- USAF RB-47 , off-shore Kamchatka Peninsula, April 18, 1955

- USAF RB-50G , Sea of Japan, September 10, 1956

- USAF C-130A , Soviet Armenia, September 2, 1958

- USAF RB-47H , Barents Sea, July 1, 1960

- USAF RB-66C , East Germany, March 10, 1964